Reality Bites

For some years I have been calling out the over-exuberant growth expectations behind Auckland’s planning. I have also argued that creating a single council to pursue a compact city strategy was wrong. First, the supercity structure was always going to increase the cost of local government while diminishing its responsiveness to the increasing diversity of communities and changing external conditions. Second, planning based on intensification and centralisation was always going to frustrate the growth it was meant to accommodate, pumping up house prices, business costs, and congestion.

These were hardly popular views, and it gives me no pleasure

to say today that the chickens have come home to roost. Emigration is rising.

Housing demand is softening, although too late to prevent a growing division between expanded renter and shrunken owner classes. The need for social housing is well up, while the already

high cost of home building keeps getting higher. (And through grandiose spending plans, Auckland Council has become a fiscal and economic liability).

Meantime, in neighbouring Australia wages are higher, house

prices and living costs lower, and the labour market buoyant, leading once

more to the loss of young and productive people across the Tasman. And,

more Aucklanders heading for the regions will compound the slump in the

residential market – in prices and in building (but not necessarily the cost of

building).

The region has for decades taken the lion’s share of the

country’s population growth, but that dominance is fast diminishing.

The labour market: pausing or turning?

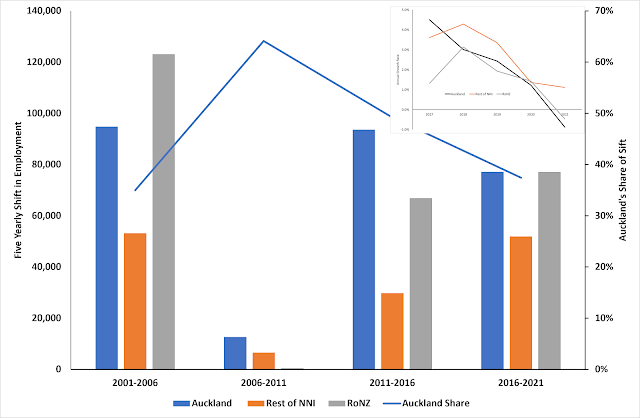

Unfortunately, the same goes for employment. Auckland’s job growth

has trailed the rest of the country since the Global Financial Crisis (Figure 1), leading national growth into negative territory

over the past five years (inset).

Figure 1: Regional Employment Growth, 2001-2021

This has not been helped by Auckland’s lagging productivity growth (Figure 2). While Wellington and Auckland still record the highest regional productivity, this is on the back of a tradition of falling primary and manufacturing jobs and increasing, well-paid white-collar employment in the business and government sectors.

Figure 2:

Auckland’s Lagging Productivity Growth

According to Statistics NZ February counts, there have been significant falls in business services, manufacturing, logistics, and Covid-impacted hospitality. Only construction and public services (including education, health and social care, and government services) held up (Table 1).

Table 1: Recent Employment Changes in Auckland

Sector | 2020-21 | |

Shift | % | |

Primary | 210 | 3.4% |

Manufacturing | -2,400 | -3.0% |

Utilities | 300 | 5.4% |

Construction | 3,600 | 5.8% |

Logistics | -4,600 | -4.6% |

Retail | 700 | 0.9% |

Hospitality | -3,000 | -5.1% |

Business Services | -5,300 | -2.6% |

Public Services | 4,100 | 2.3% |

Personal Services | -700 | -1.7% |

Total | -7,090 | -0.9% |

Structural Flaws

Unfortunately, this mix of employment is unlikely to help in the future. The downturn realised in 2021 may well prove to be a significant turning point (Figure 3).

For a start, the white-collar sectors, particularly in government and business administration, can be expected to shrink under the combined pressure of remote and flexible work practices and the loss of back-office occupations as advances in artificial intelligence automate an increasing array of transactional tasks.

Government-funded services can be expected to follow the same path, particularly with the inevitable tightening of the fiscal belt in the face of ballooning global deficits and rising interest rates.

How this will play out in the labour market – in favour of the administrators in the high rise offices or the providers on the ground – is yet to be seen. As the white-collar sectors stutter, though, the future of the labour market will rely increasingly on production and distribution, especially as construction also faces a sharp downturn.

Figure 3: Auckland’s Changing Employment Structure, 2001-2021

At the same time, possibly radical changes in world trade resulting from geopolitical upheavals and the increasing impact of climate change will favour regional economies with efficient production and distribution sectors. Among other things this is likely to sustain the movement of economically active households from Auckland to regional centres.

Time for a reset?

So here's my take on some of the hard issues facing Auckland against a background of a slowing world economy,an intensifying

climate emergency, soft if not declining population growth, and a vulnerable labour market.

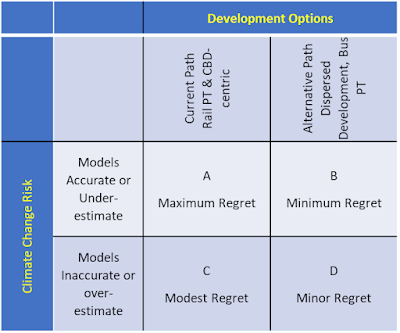

First, we have to revisit our infrastructure plans, acknowledging the vulnerability to climate change of key components, including the sewage treatment plant, airport, ports, rail, and downtown Auckland. Apart from the protective (and conservative) investment this will call for, the city needs to reduce its penchant for investment that does little more than prop up values in the central city, and instead address the liveability of the suburbs where the vast majority of people live and work.

Infrastructure investment will have to be founded on sound evidence, be economically and environmentally sustainable, minimise fiscal and physical risk, and be shaped by reason rather than dogma, sound analysis rather than bureaucratic group think.

Second, accept the logic of sustainable new suburbs, low impact housing (as opposed to multi-tiered, energy intensive, high density structures), and

detached settlements supported by

appropriately-scaled infrastructure, connected and networked by generous, multi-modal corridors.

Third, address the divisive problem of

deprivation in Auckland, which has been reinforced by backward-looking policies favouring those

who own property over those who don't; those who live in gentrified,

well-serviced inner suburbs over those who don't; office over industrial employment; and large, centralised commercial centres over accessible local neighbour centres.

Fourth, acknowledge the reality of climate change and its inevitable impact on properties and infrastructure in a city with an extensive shoreline. This may mean planning for resilience rather than containment, reducing the intensity of development in vulnerable areas among other things. The challenge is how to manage a long-term reduction of value of central and harbour edge sites over just one or two generations.

Finally, adopt a fiscally responsible approach to local government, reducing the bloated investment and operations that followed the creation of a monolithic city structure in 2010 and its quasi-commercial satellites and their opaque tolling operations.

A good start could be made by acknowledging the reality of a slow-growth outlook by dismantling the Auckland Unitary Plan and its premise that centralised activity to support the historical concentration of wealth should be sustained at all costs. Replace it with light handed planning that fosters a region of connected communities, each meeting most of the needs of its residents locally.

There is a need to provide accessible opportunities for work, play, and care in an era in which personal mobility could be compromised. This cannot be achieved seeking to contain growth (and now, perhaps, decline) in a highly centralised, high density, public transit-dependent city.