Light Rail: A solution in search of a problem

Auckland has seen that

the creation of commissions, teams, or working parties to implement

simple-minded solutions to complex problems allows little room for debate on alternatives. Like the creation of the supercity and Auckland’s Central Rail Link, the proposed CBD to Airport tunnelled light

rail is a solution in search of a problem.

In Tuesday’s NZ

Herald economist Tim Hazledine strips Auckland’s congestion problem back to basics. He raises some facts that seem to have been overlooked: the limited nature of the problem, the

availability of congestion pricing to resolve it, the changing of CBD work, the

low utility of a service stopping at 18 stations over a short distance, and

Auckland’s “topsy turvey topography”.

There's not a lot to add to

his critique, but here’s some more on the environmental issues and changes

in Auckland’s growth, both of which render the LRT already obsolete.

Climate Emergency: Yeah? Nah?…

In 2019 Auckland

Council declared a Climate Emergency. In January 2022 the Government announced new light rail (LRT) from

the CBD to Auckland Airport, flying in the face of that declaration: risk

maps (1) put the LRT terminals, the airport and the CBD’s Western Viaduct, below the annual

flood level before the end of the 60-year horizon used to justify it.

Inundation

Prospects 2080: Auckland CBD and Airport

So, there is an

elephant in the tunnel.

It gets worse.

The Minister of Transport also announced another

major construction project, a “second”

harbour crossing, predictably endorsed by lobby group, Infrastructure

New Zealand.

The new crossing will parallel the Auckland Harbour Bridge and share

its northern approach. Unfortunately, this portion of State Highway One road already floods in severe storms. Given

that it will flood more frequently as the sea level rises and storm events

increase, the planned crossing will do little for network resilience. (4)

(We should mention that there is already a

second crossing. Between West Auckland and North Shore, it will not be

directly affected by climate change because its approaches are well above sea

level).

Tunnel-vision

Acknowledging a Climate Emergency should

lead to reconsideration of urban form and infrastructure to deal with the

structural drivers of emissions. Current plans for excessive public investment will provide disproportionate private benefits to the small minority of Auckland’s households and businesses that benefit from the operation of fixed-route, heavily subsidised transit services. Turning

attention, instead, to land use and the relationship where most people live and work (which is clearly not the CBD) should lead to more much equitable urban form and investment outcomes.

The government, the council, and its agencies should be revising their long-term plans to recognise the reality of climate change and shifting urban form, and aim to reduce transport demand without penalising mobility. Instead, their aim seems to be to cement in historical city form in the face of unprecedented climate change .

The plans will seriously disrupt lives and, through poor use of capital

and crowding out better investment, undermine productivity. On the plus side (?), they should sustain an oligopolistic civil engineering and infrastructure sector and prop up CBD and on-route property values.

Incidentally, climate myopia is not confined

to the public sector. It’s fascinating to see businesses taking up new, ”green”

commercial space in downtown Auckland’s future flood zone, while vacancies increase

in the elevated uptown offices they are abandoning.

Auckland at a tipping

point

We need to acknowledge

another elephant.

With Covid people think about a new normal in terms of public health. Equally significant, though, Covid has accelerated shifts already changing Auckland’s growth path.

Consider the combined impacts of:

·

A cyclical

downturn in immigration, which commenced in 2018, accelerated under

Covid;

·

A wage-disadvantaged

economy will prolong the migration deficit beyond the “Covid effect”;

·

Technology

advances and changing work practices undermining central city growth;

·

Land,

service, and congestion costs leading to the decentralisation of industry;

·

Changes in

attitudes to work, careers, and lifestyle reshaping how and where people want

to live, and where and when they want to work;

· A continuing population push out of Auckland;

· Technology changes in the distribution of goods (bar codes, robotics,

consumer-focused logistics) and services (decentralisation and democratisation

through IT and AI);

·

An

increasingly obsolete 20th Century model of urban and commercial hierarchies behind Auckland’s long-term planning.

Auckland is unlikely to grow to match the bullish projections used by the

current crop of city planners and builders.

Nor will urban design based on debatable assumptions about where people should live

and work.

Revising urban form

- planning for dispersal

With or without climate change, it is time to ease over-investment in that ageing tiara, the city centre, and put more into our scattered diamonds, emerging urban villages, and our pearls on a string – the centres of Wellsford, Warkworth, Drury, Pokeno, Tuakau, and the like – north and south of Auckland.

It is time to focus investment on the infrastructure and amenity needs of a range of urban centers rather than on mindlessly sinking public funds into the CBD. This means developing and maintaining well-balanced, localised land use and services. On the transport front, decentralised

investment can facilitate more active travel options and demand-based vehicle

sharing. Flexible bus options can operate both within and between centres, the

latter on strong corridor connections among them.

Fortuitously, supporting dispersal within and beyond the city means spreading the risks associated with climate change and adopting defensive rather than intensification strategies on the waterfront.

Dealing with the risk of climate change

Of course, that’s just an opinion from

outside the tent.

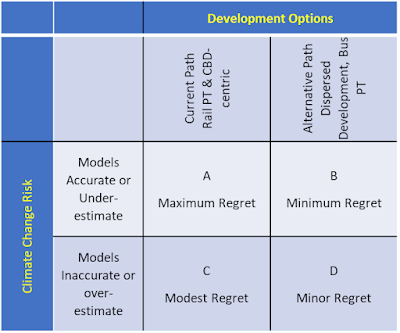

But here's my take on these diverging

scenarios in the form of a risk/regret matrix.

The risks (“How likely are the climate change projections?”) fall

on the vertical axis, the planning options on the horizontal axis (“Which

development path shall we take”?)

The case for changing direction

The current investment path (which leads to cell A or C) looks wrong. If we stay with it and the models are about right, we will write off a lot of investment and lower our ability to react to the impacts of climate change (Cell A). Even if the climate settles, we may still look back with regret at misplaced and under-costed commitments (Cell C).

If, on the other hand, we shift to dispersed and flexible investment and the climate remains benign (Cell D), we would at least have a policy framework that should cope well with slower growth and reduce inequities within the city.

Finally, if we are

fully exposed to the rigours of an unstable climate, then catering for dispersed development and opting for flexible public transport would provide the resilience and capacity to bounce back

from climate disruption (Cell B). The

consequences of climate change may not be pleasant, but we will be better

placed to deal with them. There will be regret – it’s too late to wind back the

climate change clock – but we will have done our best to minimise it.

By the way …

Globally, the money-printing

presses are grinding to a halt. The prospect that inflation will ease central

and local government deficits will be offset, in part, by rising interest

rates. Money is no longer free, or debt

without consequence. The case for major transport projects must be robust

rather than shaky, definitive rather than indicative.

Proceed with the LRT

and Auckland’s Climate Emergency will generate a fiscal crisis and see the

integrity of Auckland’s infrastructure undermined as the promise and pressures

of growth diminish, fiscal and financial liabilities increase, and the

sea encroaches.

[1] Based on the 2021 IPCC global warming consensus

[2] For example, cement releases over 0.5tCO2/tonne and steel over 1t/tonne produced.

[3] The Technical Appendices behind the Indicative Business

Case,

including Carbon Assessment, are not yet published.

[4] Flooding could be offset by extensive and expensive

raising of the road (State Highway One), some of which will be needed anyway to

keep the existing bridge functional. Expanding it at the same time, over 8km of

vulnerable shoreline, raises a whole lot more issues (and costs). though.