In 1974 central planners came up with the idea that development of the small rural service centre, Rolleston, 25km from the CBD, as a “new town” would help accommodate the growth of Christchurch City. Not long living in the UK at the time, I had looked closely at the new towns north and east of London and argued that the initiative was unjustified.

The post-war new towns in South East England were intended to take up some of the growth pressures on London, containing its expansion and relieving the highly stressed housing situation in the capital. The new towns were intended to cater for London's overspill, but to be as self-sufficient in employment terms as possible. There was also a commitment to a “mixed social class”, a reaction against the social problems associated with large, undifferentiated working class housing estates in London. [1]

The new towns were built around long-standing garden city principles, but to a young kiwi did not appear particularly attractive. To my mind, it made little sense to transfer the concept to Christchurch, with its more modest growth and scale, different housing and lifestyles, wide open spaces, mountain vistas, and ready access to the coast.

|

| Rolleston Vistas (Images, Steve Busson) |

Rolleston new town was a solution in search of a problem. It did not go ahead.

But that was then

It did not stop Rolleston growing in its own right, especially over the past fifteen years, nor the other rural towns of Canterbury. Consequently the districts surrounding Christchurch City, Waimakariri and Selwyn, have been among the country’s fastest growing in recent times, a reflection of the attraction of their small towns for people seeking an affordable lifestyle, a sense of community, and the convenience of proximity to Christchurch City.

Perhaps now is the time to revisit the idea of coordinated growth focused on these small settlements close to Christchurch, or even in greenfield sites that offer better prospects of geological stability than the city’s ruptured and traumatised eastern suburbs. Can east move west?

Any such solution cannot be simply mandated and imposed on the suffering communities east of the Christchurch CBD today: if people displaced by the earthquakes of the past nine months are to stay in and around the city, they need to have a say in where and what sort of community they might move to. The sort of wholesale dislocation they face may require the powers and capacity of central government to initiate and facilitate solutions, but the community has to be central to any relocation exercise. And perhaps whole community solutions are required, not sot hat they prevent individuals from taking their own measures, but which enable communities to work together to find solutions that they may share.

What I am suggesting is the transfer of communities -- groups of households -- into the 21st century equivalent of the new town west of Christchurch.

The institutional framework may have be revamped for the purpose – the Earthquake Commission, the insurance companies, government agencies, even the banks working together to best discharge their individual and joint liabilities and responsibilities; while the people and professionals work together to shape the city of the future. There may be an opportunity to work together to create an affordable and very liveable alternative.

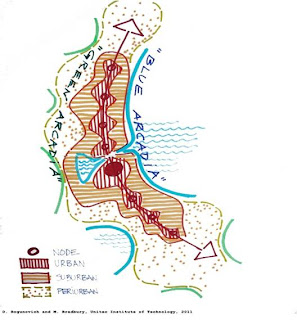

The township alternativeI have already suggested that Christchurch’s best shot may be decentralised intensification, suburbs focused on human scale community centres, linked by wide avenues or boulevards. Add to this mix subtly worked new towns or villages, not of the scale of a Crawley, Basildon, or Stevenage in southeast England, but something fitting the Canterbury landscape and Christchurch people.

Such developments bring with them real lifestyle advantages in an attractive physical setting. This is what the similarly attractive shire of Margaret River in Western Australia is doing with its town site and rural hamlet strategies; establishing a human scale, low impact alternative to extensive urbanisation in a popular growth area. It is doing this, interestingly, with the help of Auckland-based Common Ground urban designers.

Tying it together the Curitiba wayWe can add to this vision. Away from the eastern suburbs the garden city survives around its avenues, as attractive as ever. Its suburban and town centres are likely to play a bigger role, though, with employment and retailing potentially dispersed throughout the city even more in the future than in the past.

That is not to detract from the CBD. Christchurch has a commitment to rebuilding its CBD as the heart of the region. This may be in a moderate density, medium-rise manner (and let’s face it, high rise building in Christchurch has been the exception in the past, and will be a lot harder to justify in the future).

What we will have to think about, though, is how to tie the CBD back to more self-sufficient neighbourhoods, and to growing satellite villages and townships. Sam Coutts drew our attention to what Curitiba has achieved. This is a sustainable city built around wide boulevards that provide green corridors and capacity for a variety of transport modes (the city relies heavily on bus transit), green spaces and extensive parks and gardens to manage and contain floods and cater for a population living in relatively high density housing, and efficiently networked services. Even though Curitiba is bigger than Christchurch (with a population approaching 2,000,000), it offers ideas and inspiration about what can be achieved in a sustainable 21st century city located ina dynamic physical environment.

This is nowI sometime wonder whether as it has grown, urban planning in places like New Zealand, with advanced urbanisation, maturing cities, modest growth, and reasonable levels of wealth and income, has had too little to do. In seeking out problems to solve it has concentrated increasingly on process and minutiae (in the name of growth management, perhaps?)

But today Christchurch has real problems, and they are big ones. It is time to rise above the detail, to cut through undue process, and to act with a combination of vision and conviction. Now the public and private sectors, citizens and their institutions need to put practical solutions in place. There do not even appear to be many options to debate. Going west, the 1974 solution, may just be the one Christchurch has to adopt in 2011.

[1] Heraud B (1966) “The New Towns and London’s Housing Problem” Urban Studies, 2, 8-22